That thought is the beginning of every project tackled by the Iowa Medical Innovation Group (IMIG), a University of Iowa program that brings together students from the colleges of law, medicine, engineering and business to develop an idea for an original medical device. From design, to prototype, to business plan and patent, IMIG students collaboratively work to find a better way of doing “this.”

'First do no harm'

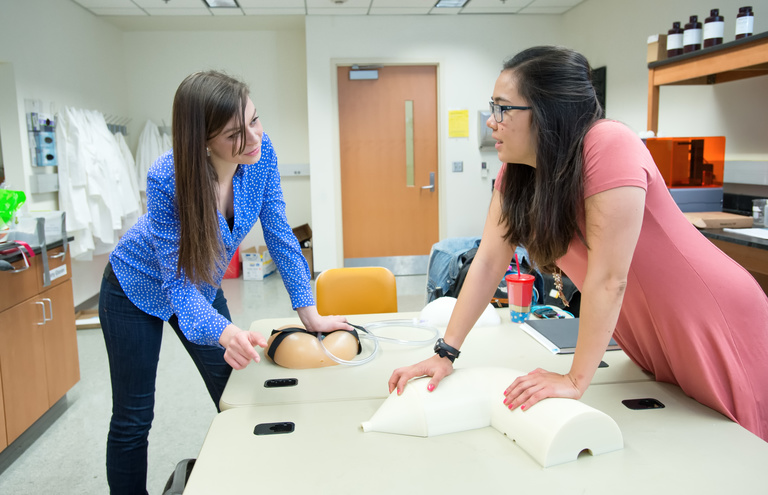

In a basement computer lab in the Seamans Center for the Engineering Arts and Sciences, four heads cluster around a single laptop watching a YouTube video. Rather than the Evolution of Dance, the undergraduate IMIG engineering team of Molly Berringer, Andrea Caceres, Claire Castaneda and Amanda Smith are watching videos of a medical procedure to correct an intussusception. Usually occurring in children under age 5, intussusception occurs when a portion of the bowel folds in on itself like a telescope. It’s incredibly painful and requires immediate medical intervention.

As a new fellow at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Manish Bajaj, M.D., observed the traditional intussusception procedure used to correct this collapsing of the bowel. In layperson terms, air is forced into the bowel to straighten it back into place. The method requires a gentle and consistent force of air pressure – air delivered by an air pump and air pressure maintained by, well, any means necessary.

“The success of the procedure depends on keeping an air tight seal around the child’s bottom,” explained biomedical engineering student Claire Castaneda who worked on the IMIG intussusception project. “To keep the air tight seal, clinicians will use duct tape or pull someone else into the room whose job is just to hold things in place. If you watch the procedure on YouTube, you notice everyone does it a little differently and it’s super ad hoc.”

If this procedure fails, the patient has to undergo bowel surgery, which is significantly more risky and involves a longer and more difficult recovery. Observing the absurdity of the struggle to hold a child’s bottom together, Bajaj had his “there’s got to be a better way to do this” moment and started a conversation with his attending Michael D’Alessandro, M.D., on how to improve the procedure.

"The key ethical principle that drives the practice of medicine is primum non nocere, or first, do no harm,” said D’Alessandro. “Therefore in medicine we are always striving to develop new treatments for patients that are quicker, less painful, safer and easier to do consistently."

Bajaj ultimately presented this conundrum to the UI Department of Biomedical Engineering, which fields unmet clinical needs or problems with the status quo way of doing a specific procedure before turning them over to senior undergraduate biomedical engineering students. These become the subjects of the students’ required senior capstone design series, a two-semester project where students design and test prototype medical devices.

Open to only 16 senior biomedical engineering students per year, IMIG takes these senior projects to the next level by teaming the engineering students up with the same players they would work with in real world of medical device development: attorneys, doctors and business people.

“I feel like IMIG sets you up for success in the medical device industry because I am already working with a multi-disciplinary team of law, marketing and finance people as an engineer,” said 2016 biomedical engineering graduate Amanda Smith, who went on to land a job with the medical device company Boston Scientific. “Not only are your teammates a great resource, but it is representative of the actual medical device industry because you work on teams with a variety of backgrounds and experiences. Being on a team of such different strengths pushed me to learn a variety of ways to communicate and leverage everyone's strengths.”

The value of the multi-disciplinary teamwork experience is echoed by a graduate of one of the original IMIG groups, Riley Lind, a 2012 Tippie College of Business MBA graduate and technical product manager at Volkswagen of America, Inc.

“One of the most important things I learned through IMIG was how to communicate with engineers, doctors and business people,” said Riley. “That's one of the biggest challenges I have in my current role as a project manager as well. I've worked one-on-one with everyone from the plant CEO to the guy who packs the boxes. What IMIG helped me cultivate was the ability to work with all of these people and really know my audience. It helped me to put myself in their position to explain why I need something or why something is an emergency to me while to them it may not seem like a big deal.”

From concept to 'crazy design'

For rising third-year law students Judy He and Sarah Dickhut, this meant taking big picture principles of intellectual property, business formation, regulatory compliance, transactions and licensing, and determining what impacts that had for their IMIG team. UI College of Law Professor Jason Rantanen, the IMIG faculty advisor for the law school, said IMIG simulates the holistic legal services that an in-house counsel would provide to a medical device company.

“You have a setting where law students have learned a fair amount of knowledge, how to analyze problems rigorously and how to deal with unfamiliar situations,” said Rantanen. “And now they get a chance to try that out in a relatively safe environment. This is not going out on day one and working for Johnson & Johnson where, if you make a mistake, people could lose their jobs over it. This is a classroom environment. Because of that it gives the students an opportunity to learn and try out their skills in an educational setting.”

In IMIG that usually starts with a review of patented prior art to make sure engineered innovations aren’t disqualified because someone else has already come up with it. For the uninitiated, it can be a confusing and laborious process and non-IMIG senior biomedical engineering design students have to hack it on their own. Engineering students Castaneda and Smith both reported the relief they felt in having He and Dickhut on their team, breaking down the legal jargon into “This is what you can do. This is what you can’t do.”

Funding for IMIG is provided by the UI John Pappajohn Entrepreneurial Center with support from donors including the William A. Steele Foundation which allowed the engineering side of the team to focus on innovation rather than penny pinching. Engineering projects involve a lot of trial and error and the additional research dollars allowed the team to have more financial wiggle room when purchasing valves, silicon and other materials as they came up with new ideas. With the MBA students managing commercialization efforts and the budget, the engineering students could focus on the prototype humming off the 3D printer.

“The resources that IMIG gave us made us more bold and forward thinking with our design,” said Castaneda. “It took so much pressure off of us in an intellectual sense and in a financial sense so that we could do what we always wanted to come to school to do: bang out a crazy design.”

Building prototypes and careers

The “crazy design” developed by this IMIG team included an automatic pump to replace the old manual one and a special belt that provides access to the bowel while also forming the critical airtight seal. With assistance from the UI Research Foundation, the IMIG team and D’Alessandro and Bajaj filed a provisional patent application on the devices. While the students will take the next steps in their career before being able to see what comes of their brain children, they leave with invaluable experience and a potentially impressive item on their resumes.

Though the IMIG program is only six years old, two promising medical devices developed by earlier IMIG groups have evolved into spin-off companies supported by early funding from the UI Office of Research and Economic Development’s UI Ventures program: Voxello and Bloodworks.

Communication Sciences and Disorders Professor Emeritus Richard Hurtig worked with an IMIG team to build an early prototype of the noddle™, a medical device that allows patients with physical impairments to communicate with hospital staff. The prototype won the Hubert E. Storer Engineering Student Entrepreneurial Start-up Award and, with support from UI Research Foundation and the John Pappajohn Entrepreneurial Center, filed an invention disclosure and formed the company Voxello to continue developing the device.

Tomorrow if you woke up in an ICU at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics with a endotracheal tube down your throat, the noddle™, in clinical trials at the hospital, will be there to allow you summon help and communicate with a nurse or other care providers via small movements like a tongue click, hand movement or eye blink. Voxello is now in the process of submitting the final documentation for FDA clearance as a medical device. Clinical trials are going to be extended to other major medical centers around the United States.

Hurtig said more than 3.9 million patients in United States hospitals each year are limited in their ability to communicate with care providers. Ultimately, improved patient-provider communications provided by Voxello technology should drastically reduce preventable medical errors, lower health care costs and improve patient satisfaction.

“The success of Voxello illustrates how the IMIG program can provide students and their mentors the opportunity to work collaboratively to develop solutions that can dramatically improve the lives of patients,” said Hurtig. “When I met the IMIG students and we began our project, we didn’t envision being the founders of a medical device company, but that is what happened.”

Castaneda holds out hope that their IMIG project will find similar success. “I hope it does because I really do believe in this design,” said Castaneda. “I believe it is a better avenue. We are optimistic we can get it licensed.”

The creative, entrepreneurial spirit infusing IMIG gives UI students invaluable experience, it fosters interdisciplinary collaboration between faculty, and it furthers the University of Iowa mission of creating innovative, life-changing research that has a direct impact on the health and economic wellbeing of our communities.

IMIG takes “there’s got to be a better way to do this” and answers: “Yes. There is.”

The UI Research Foundation is part of the Office of the Vice President for Research and Economic Development, which provides resources and support to researchers and scholars at the University of Iowa and to businesses across Iowa with the goal of forging new frontiers of discovery and innovation and promoting a culture of creativity that benefits the campus, the state, and the world. More at http://research.uiowa.edu, and on Twitter: @DaretoDiscover.

Photos (from top): IMIG students Molly Berringer (left) and Claire Castaneda discuss a prototype for treating intussusception; formulas related to the prototype penned on a piece of paper. Photos by Justin Torner, University of Iowa Office of Strategic Communication.